On 15 October 1987 at 19:13 an ATR 42 with 37 people on board, operated by the Italian company "Aero Trasporti Italiani", takes off from Milan-Linate directed at Cologne/Bonn airport. After twenty minutes, the plane crashed on Mount Crezzo.

On 22 March 1928, a Fokker F28 attempted take-off from LaGuardia Airport in New York, but was unable to gain altitude and crashed into the sea.

These two accidents, apparently unrelated to each other, were caused by a common killer: the ice.

If we were to list all aircraft accidents caused by the formation of ice, probably a single post would not be enough.

The danger of ice for air transport involves many aspects:

Speaking of ice that can be deposited on the structure of the airplane, fuselage, wings and tail, there are generally recognized two types of ice, rime ice and glaze ice.

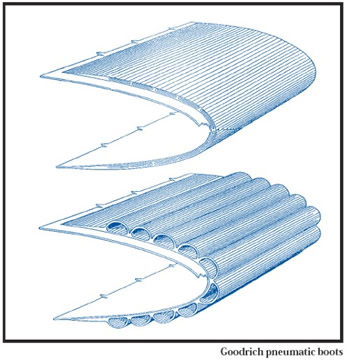

The rime ice is less dangerous: it is a very friable kind of ice, which tends to peel off easily as soon as deicing devices are employed (typically a heated surface or a mechanical mechanism that detaches the ice of the wings, typically an air chamber that can inflate and deflate on the edge of the wing, de-ice boots). It is also easily visible, as it is very opaque. It is generally formed when supercooled water droplets (that is water still liquid at temperatures below zero degrees), impacting on the surface of the wing, freeze instantly.

This occurs mainly when the outside temperature is well below zero degrees.

The glaze ice is much more subtle. It is in fact a transparent and very compact layer that can completely cover the wing. It is very difficult to detect because of its physical characteristics and it is also more difficult to remove. It is produced when the drops of water, instead of instantly freezing, have time to spill out onto the surface. This implies that this type of ice can often thicken even in areas not protected by deicing systems or inside joints and mechanical mechanisms, covering all the wing in addition to the leading edge. It is generally formed when the ambient temperature is a little lower than zero degrees, and so the drops have all the time to freeze slowly and, in the meantime, even to join among them producing a compact layer.

The ice in the carburetor is a risk mainly for small piston aircraft.

As seen in the image , the air coming from the filter is forced to pass in a narrowing (Venturi), where it expands quickly sucking the fuel. However, the rapid expansion of a gas generally produces a decrease in temperature (that's how the fridge works!), which can drop down to 15 ° C below the outside temperature. If the air contains a lot of moisture, there is the possibility that it can freeze in the carburetor thus stopping the flow of fuel and air to the engine.

To prevent this problem, a good part of the aircraft are equipped with a control for the hot air to the carburetor , which has precisely the function to preheat the air before it gets to the throttle valve, thus preventing the formation of ice.

However, it is often not so simple to realize what is going on before the engine stops!

A first indication of a problem of ice is given by the irregular operation of the engine, with a sharp drop in rpm. In this case, it is essential to immediately enter the hot air in and to get out as soon as possible of the unfavorable conditions that are encountered, for example losing altitude as rapidly as possible .

The hot air will produce as a first effect a further decline of rpm, since the hot air is less dense and therefore also less saturated with oxygen .

However the rpm will quickly to rise again once the ice will begin to melt.

It is also important to keep the flow of fuel well above the minimum. If you are over the mountains and is therefore not possible an emergency descent, you should extend the flaps and slow down, so as to enter in a condition in which to maintain level flight you need more power (slow flight regime), and then you can increase the flow of fuel as large as possible to mitigate the problem.

Obviously, the best safety measure to be taken is just one: to avoid finding themselves in conditions of icing!

The aircraft involved in commercial traffic obviously can not continually change course or delay the flight for each meteorological problem: this is why they are equipped with extremely complex anti-icing and de-icing systems and, above all, the pilots who operate them have received specific training (anti-ice systems prevent ice formations, de-ice devices break the ice already formed).

The same can not be said for those flying for pleasure, which often does not even have an instrument rating! To avoid flying in clouds means certainly to reduce the chance of ice forming on the wings to a minimum, as it is right in the clouds that more often you can find the prevailing weather conditions for the formation of ice on aircraft surfaces.

The ice to the carburetor is much more insidious, as it can be formed also with environmental temperatures much above zero and in the absence of visible moisture. In this case the only defense is the preparation of the pilot, who must be aware of the danger that could be met (have a look at the difference between dew point and outside temperature!) and not get caught unprepared at the first signs of engine problems.

p.s. All the pictures are taken from the web, I have no rights on them!

Il 15 ottobre 1987 alle ore 19.13 un ATR 42 con 37 persone a bordo, operato dalla società Aero Trasporti Italiani, decolla da Milano-Linate diretto all'aeroporto di Colonia/Bonn. Dopo venti minuti l'aereo si schiantava sul Monte Crezzo.

On 22 March 1928, a Fokker F28 attempted take-off from LaGuardia Airport in New York, but was unable to gain altitude and crashed into the sea.

These two accidents, apparently unrelated to each other, were caused by a common killer: the ice.

If we were to list all aircraft accidents caused by the formation of ice, probably a single post would not be enough.

The danger of ice for air transport involves many aspects:

- It can deposit on the wings, thus affecting negatively the aerodynamic, increasing the stall speed and also quite often making extremely difficult to exit a stall, as in the two cases above (you can see here what is a stall and how to recover from it: http://yokeandrudder.blogspot.it/2013/06/stalls.html);

- After it is deposited it may detach from the wings and hit the engines, as in the case of the Scandinavian Airlines 751 flight on 27 December 1991;

- It can obstruct and block the Pitot tube, the device used in any plane, even ultra-light, to provide speed data. The obstruction of the Pitot tube, due to the ice, is one of the possible causes of the crash of Air France flight 447 in the Atlantic Ocean;

- In the case of piston engine aircraft, as are most of the small general aviation planes, ice can obstruct the throttle valve of the carburetor, thereby causing an engine failure (this is what happens when the engine stops: http://yokeandrudder.blogspot.it/2013/05/when-that-one-engine-stop-blowing.html)

Speaking of ice that can be deposited on the structure of the airplane, fuselage, wings and tail, there are generally recognized two types of ice, rime ice and glaze ice.

The rime ice is less dangerous: it is a very friable kind of ice, which tends to peel off easily as soon as deicing devices are employed (typically a heated surface or a mechanical mechanism that detaches the ice of the wings, typically an air chamber that can inflate and deflate on the edge of the wing, de-ice boots). It is also easily visible, as it is very opaque. It is generally formed when supercooled water droplets (that is water still liquid at temperatures below zero degrees), impacting on the surface of the wing, freeze instantly.

This occurs mainly when the outside temperature is well below zero degrees.

(Deicer boots)

The glaze ice is much more subtle. It is in fact a transparent and very compact layer that can completely cover the wing. It is very difficult to detect because of its physical characteristics and it is also more difficult to remove. It is produced when the drops of water, instead of instantly freezing, have time to spill out onto the surface. This implies that this type of ice can often thicken even in areas not protected by deicing systems or inside joints and mechanical mechanisms, covering all the wing in addition to the leading edge. It is generally formed when the ambient temperature is a little lower than zero degrees, and so the drops have all the time to freeze slowly and, in the meantime, even to join among them producing a compact layer.

The ice in the carburetor is a risk mainly for small piston aircraft.

As seen in the image , the air coming from the filter is forced to pass in a narrowing (Venturi), where it expands quickly sucking the fuel. However, the rapid expansion of a gas generally produces a decrease in temperature (that's how the fridge works!), which can drop down to 15 ° C below the outside temperature. If the air contains a lot of moisture, there is the possibility that it can freeze in the carburetor thus stopping the flow of fuel and air to the engine.

To prevent this problem, a good part of the aircraft are equipped with a control for the hot air to the carburetor , which has precisely the function to preheat the air before it gets to the throttle valve, thus preventing the formation of ice.

However, it is often not so simple to realize what is going on before the engine stops!

A first indication of a problem of ice is given by the irregular operation of the engine, with a sharp drop in rpm. In this case, it is essential to immediately enter the hot air in and to get out as soon as possible of the unfavorable conditions that are encountered, for example losing altitude as rapidly as possible .

The hot air will produce as a first effect a further decline of rpm, since the hot air is less dense and therefore also less saturated with oxygen .

However the rpm will quickly to rise again once the ice will begin to melt.

It is also important to keep the flow of fuel well above the minimum. If you are over the mountains and is therefore not possible an emergency descent, you should extend the flaps and slow down, so as to enter in a condition in which to maintain level flight you need more power (slow flight regime), and then you can increase the flow of fuel as large as possible to mitigate the problem.

Obviously, the best safety measure to be taken is just one: to avoid finding themselves in conditions of icing!

The aircraft involved in commercial traffic obviously can not continually change course or delay the flight for each meteorological problem: this is why they are equipped with extremely complex anti-icing and de-icing systems and, above all, the pilots who operate them have received specific training (anti-ice systems prevent ice formations, de-ice devices break the ice already formed).

The same can not be said for those flying for pleasure, which often does not even have an instrument rating! To avoid flying in clouds means certainly to reduce the chance of ice forming on the wings to a minimum, as it is right in the clouds that more often you can find the prevailing weather conditions for the formation of ice on aircraft surfaces.

The ice to the carburetor is much more insidious, as it can be formed also with environmental temperatures much above zero and in the absence of visible moisture. In this case the only defense is the preparation of the pilot, who must be aware of the danger that could be met (have a look at the difference between dew point and outside temperature!) and not get caught unprepared at the first signs of engine problems.

p.s. All the pictures are taken from the web, I have no rights on them!

--------------------------------------

Il 15 ottobre 1987 alle ore 19.13 un ATR 42 con 37 persone a bordo, operato dalla società Aero Trasporti Italiani, decolla da Milano-Linate diretto all'aeroporto di Colonia/Bonn. Dopo venti minuti l'aereo si schiantava sul Monte Crezzo.

Il 22 marzo 1928 un Fokker F28 tentò il decollo dall'aeroporto LaGuardia di New York ma non riuscì a prendere quota e finì per schiantarsi in mare.

Questi due incidenti apparentemente slegati tra loro sono stati causati da un killer comune: il ghiaccio.

Se dovessimo elencare tutti gli incidente aerei causati dalla formazione di ghiaccio probabilmente un solo post non servirebbe.

Il pericolo del ghiaccio per il trasporto aereo coinvolge molti aspetti:

- Può depositarsi sulle ali, inficiandone irrimediabilmente l'aerodinamica, aumentando la velocità di stallo anche di parecchio e rendendo spesso estremamente difficoltosa la rimessa, come nei due casi sopra riportati;

- Dopo essersi depositato può staccarsi dalle ali andando a colpire i motori, come nel caso del volo 751 della Scandinavian Airlines del 27 dicembre 1991;

- Può intasare e bloccare il tubo di Pitot, lo strumento utilizzato in qualsiasi aereo, anche ultraleggero, per fornire i dati di velocità. L'ostruzione del tubo di Pitot dovuto al ghiaccio e una delle possibili cause dello schianto del volo AirFrance 447 nell'oceano Atlantico;

- Nel caso degli aerei con motore a pistoni, come lo sono la maggior parte dei piccoli aerei da turismo dell'aviazione generale, può ostruire la valvola a farfalla del carburatore, causando così una piantata motore.

Parlando del ghiaccio che può depositarsi sulle strutture dell'aereo, fusoliera, ali e coda, vengono generalmente riconosciuti due tipi di ghiaccio: il ghiaccio granuloso e il ghiaccio vetrone.

Il ghiaccio granuloso è quello meno pericoloso: si tratta di ghiaccio molto friabile, che tende a scrostarsi abbastanza facilmente in seguito all'azionamento dei dispositivi antighiaccio (costituiti in genere o da una superficie riscaldata o da un meccanismo meccanico che stacca il ghiaccio delle ali, in genere una camera d'aria che può gonfiarsi e sgonfiarsi sul bordo d'attacco dell'ala). E' inoltre facilmente visibile, in quanto molto opaco. Si forma in genere quando delle gocce d'acqua sopraffuse (cioè ancora liquide a temperature inferiori agli zero gradi) impattano sulla superficie dell'ala ghiacciando istantaneamente. Questo avviene principalmente quando la temperatura esterna è di molto inferiore agli zero gradi.

Il ghiaccio vetrone è molto più subdolo. Costituisce infatti uno strato trasparente e molto compatto che ricopre completamente l'ala. E' molto difficile da individuare proprio per le sue caratteristiche fisiche ed è anche più difficoltoso da rimuovere. E' prodotto quando le gocce d'acqua invece di congelare istantaneamente hanno il tempo di spandersi sulla superficie. Questo comporta che questo tipo di ghiaccio può spesso addensarsi anche nelle zone non protette dall'antighiaccio o all'interno di giunture e meccanismi meccanici, coprendo tutta l'ala oltre che il bordo d'attacco. Si forma in genere quando la temperatura ambiente è di poco inferiore agli zero gradi e quindi le gocce hanno tutto il tempo di congelare lentamente e nel frattempo magari anche di unirsi tra di loro producendo uno strato compatto.

Il ghiaccio al carburatore costituisce un rischio principalmente per i piccoli aerei da turismo.

Come si vede nell'immagine, l'aria proveniente dal filtro è costretta a passare in una strozzatura (Venturi) dove si espande velocemente risucchiando la benzina. Tuttavia l'espansione rapida di un gas produce generalmente una diminuzione di temperatura (è così che funziona il frigorifero!), che può scendere anche di 15°C rispetto quella esterna. Se l'aria contiene molta umidità, c'è quindi la possibilità che questa possa congelare nel carburatore bloccando l'afflusso di carburante e aria al motore.

Per prevenire questo problema buona parte degli aerei sono dotati di un comando per l'aria calda al carburatore, che appunto ha la funzione di preriscaldare l'aria prima che arrivi alla valvola a farfalla impedendo così la formazione di ghiaccio. Tuttavia spesso non è così semplice rendersi conto di quello che sta succedendo prima che pianti il motore! Una prima avvisaglia di un problema di ghiaccio è data dal funzionamento irregolare del motore, con un netto calo di giri. In questo caso è fondamentale inserire immediatamente l'aria calda e uscire il prima possibile dalle condizioni sfavorevoli che si sono incontrate, ad esempio perdendo quota il più rapidamente possibile. Inserire l'aria calda produrrà come primo effetto un ulteriore calo di giri, poiché l'aria calda è meno densa e quindi anche meno satura di ossigeno. Tuttavia i giri riprenderanno rapidamente a salire una volta che il ghiaccio inizierà a sciogliersi.

E' anche fondamentale tenere il flusso di carburante ben al di sopra del minimo. Se ci si trova in montagna e non è quindi possibile una discesa di emergenza, estendere i flaps e rallentare, in modo da entrare in una condizione in cui per mantenere il volo livellato serva più potenza (secondo regime) e quindi il flusso di carburante sia il maggiore possibile, può permettere di mitigare il problema.

Ovviamente la migliore misura di sicurezza da intraprendere è una sola: evitare di ritrovarsi in condizioni di formazione di ghiaccio!

Gli aerei che operano nel traffico commerciale ovviamente non possono continuamente cambiare rotta o sospendere il volo per ogni problema meteorologico: per questo sono dotati di sistemi antighiaccio estremamente complessi e, soprattutto, i piloti che li operano hanno ricevuto un addestramento specifico.

Lo stesso non può dirsi per chi vola per piacere, che spesso non ha nemmeno l'abilitazione al volo strumentale! Evitare di volare in nube vuole sicuramente dire ridurre la possibilità di formazione di ghiaccio sulle ali ai minimi termini, in quanto è proprio dentro le nubi che spesso si ritrovano le condizioni meteorologiche prevalenti per la formazione del ghiaccio sulle superfici dell'aereo.

Il ghiaccio al carburatore è molto più insidioso, in quanto può formarsi anche con temperature ambientali molto superiori allo zero e in assenza di umidità visibile. In questo caso entra in gioco la preparazione del pilota, che deve essere conscio del pericolo a cui va incontro e non farsi trovare impreparato ai primi segnali di problemi al motore.

Thanks for and informative article - I'm adding it to my study materials for ice and rain protection.

ReplyDeleteI hope it will be useful :)

ReplyDelete